Whether in Canada, Australia, Scandinavian countries, or even Switzerland, the process remains the same: an authority—Church, State, or their alliance—takes hold of children from a minority population with the aim of erasing their cultural identity to replace it with the dominant culture. This program is summarized by the three verbs "educate, evangelize, colonize," which form the subtitle of 'Allons enfants de la Guyane.' , written by Hélène Ferrarini, and the possibility of this documentary project in French Guiana. This investigation, published last year, reveals a concealed aspect of the recent history of this French department located in the Amazon and poorly understood.

This documentary work is meant to show that, for almost a century, “Amerindian” children and, to a lesser extent, Maroon descendants of African slaves, were taken away from their families and villages to be interned in homes run by religious authorities. While the last institutions of this kind closed their doors in Canada some thirty years ago, Amerindian homes in French Guiana persisted until very recently. In fact, there is still one in operation in 2023 in Saint-Georges-de-l'Oyapock, albeit on the verge of closure.

Hunted by the gendarmes

Since the 1930s, priests and nuns have gathered children as young as 5 or 6, sometimes even 2 or 3 years old, and kept them within the homes until the end of their schooling. From 1949, the territory became a French department: the Church and the secular Republic now collaborated in this deculturation enterprise. It was the gendarmes who would search the villages for runaways or threaten recalcitrant parents with imprisonment. The Kali'na population, already weakened and fearful, struggled to resist the pressures.

Over nearly a century, all families saw one or more children sent to the homes. Even if these children returned to their families for brief stays, they forgot their mother tongue and lost the familiarity with the environment upon which the education of these hunter-fishermen relied: "Observing, looking, breathing, feeling, speaking, repeating the gestures I had memorized, that was my school, and one day I was told that it was not a good school," recalls jurist and indigenous activist Alexis Tiouka in his preface, adding, "It was a policy of assimilation without return." He passed away in late November 2023.

Pioneering work

Feelings of shame regarding one's origins, humiliating punishments, beatings, food deprivation, the pain of becoming a stranger in one's own family—these testimonies are deeply moving. As Alexis Tiouka puts it, "They wanted to kill the Amerindian but keep the man": to employ them as lumberjacks, laborers, or domestic workers.

Denial and silence

The movement initiated by Hélène Ferrarini's investigation will undoubtedly see developments. Contacted by phone, the author notes that the Grand Council of Elders and other indigenous associations want to initiate the legal process of acknowledging the violence endured, aiming for the establishment of a Truth and Reconciliation Commission. However, she adds, on the side of the authorities, the newly arrived bishop denies the events, and the silent prefecture shows discontent through administrative blockades.

Despite its differences, the picture painted by the situation resembles in many ways the atrocities Canada acknowledged and for which the government and Church have apologized. French Guiana, and consequently France, cannot avoid taking a stance on these practices and finding a way for different cultures populating the territory to coexist.

NOTES:

No one can deny France and North America have had a long and violent history with their colonialism, while the last Canadian residential school closed in 1997, French indigenous communities within the former colony of French Guiana still suffer from colonial era institutions that never went away. Such is the case with its last active residential school.

In the discrete rainforest of French Guiana, a department of France that is generally regarded as either a green hell on earth, or as a platform for its european rocket launcher, two thousand indigenous children of the headwaters of the Amazon were taken away from their families, forced by the state and the church. There would ensue a mentally and physically violent campaign, in what is colloquially called a residential school, or a "Home". The goal was to evangelize them through a system designed to weaken and permeate the bond between family, children and their rainforest-bound memories and culture.

The first Home of Mana was built in 1935, the goal back then was clear, missionaries being unable to convert the local indigenous communities to religion to a European way of life, figured they were able to take children from indigenous villages and convert them from a very young age to the education desired.

France not only acted as a facilitator in that regard but it legitimized and gave away the necessary resources to the church to achieve what could be considered a large scale cultural genocide .

As Alexis Tiouka, a renown kali’na activist said “The goal was to kill the indian and keep the man”. To that end, there were several tools put in place by both the church and the state; First, children were taken away from as young as possible. Ideally 3 to 4 year olds so that their knowledge of their culture and language were muddled and easy enough to forget over time. The families who opposed the practice would be retaliated against by the missionaries commissioning the local police to forcibly remove the children away from their families or at least coerce them into doing so with the threat of financial penalties or prison.

Both French Indigenous residential schools and Canadian Indigenous residential schools were institutions established by their respective governments to assimilate Indigenous children into Western culture, but there were some key differences between them.

In France, Indigenous children were primarily sent to boarding schools run by religious organizations, rather than directly by the government. These schools were established in the late early 20th centuries yet still remain today, and were designed to "civilize" Indigenous children and strip them of their Native identity.

In Canada, Indigenous residential schools were imposed by the government and operated from the 19th century until the 1990s. These schools were part of a larger government policy of assimilation and were often run by the church. The Canadian schools were notoriously harsh, with physical and sexual abuse being common.

While both French and Canadian Indigenous residential schools were aimed at assimilating Indigenous children into Western culture, the French schools were less loosely controlled and more discreet and subtle about their abuses.

To this day, while only the last residential school remains active on French soil, the abuses themselves have become increasingly more hidden as scrutiny about the situation has dramatically increased in the past year.

The violence the children of the homes would face was of many natures, but was mainly of three types: familial, the physical, or cultural.

The children currently going to the residential school are children of the village of Trois-Saut, a remote village located 3 days away. Due to the distance, lack of middle school in the village, and the constitutional obligation parents have to send their children to school, they do not have a choice but to send their children away to the only place able to receive them.

When the children arrive, they have to face a new education that deprives them of everything they’ve received up until now, the warmth of a family, the familiarity of their foods and traditions, the presence of a community. Many children cannot bear the change of scenery and fleeing is a frequent phenomenon. Because of these frequent acts of rebellion they are often punished by the nuns in charge.

Such is the story of Dylan, a now-17 year old from the Wayapi people who spent 3 years at the residential school. Being from Trois-Saut, he was at first delighted about the change. Despite the presence of cold and harsh new “parents'', the newness of it was an attractive prospect from the get go. But as time went on, he quickly realized his days would be far more difficult than anticipated. At 13 years old, he had to see his classmates, friends, and community fall under the recurring punishments of the nuns. He himself would be a victim of it. When asked if he already received physical punishment, yes, he nodded. When asked how he felt when it would happen “I was angry, a lot of the time I wanted to hit her back.”, he replies. He and other indigenous kids from the residential school had to steal food from the pantry because the nuns would regularly withhold food from them if they misbehaved. “If you’re punished it’s forever” he adds. The nuns had, and still have, a tight grip over their education and to this day limit the usage of their ancestral knowledge, “If we were between us we’d speak wayapi but if not we had to speak french (…) we’re told we have to speak french. (…) she’d tell us ‘speak french’.” he tells me. At the age of 16, he was able to leave as he started high school in a different place. But to this day it’s difficult for him to reconcile with what happened.

Since the children of the residential school are from Trois-Saut, during back to school time, their families go through a 3 day long journey to St-Georges that can cost up to 2 thousands euros to drop their children who’ll stay there for the next few years. They gather in St-Georges in flocks for a brief time and then go back home on that same journey. None of the children going to the residential school will be able to talk to their parents for months due to the lack of reception/internet in Trois-Saut.

When children of either the residential school of St-Georges or the host families of the littoral are kicked out of their place of stay by either the nuns/priests, parents have no way of knowing what happens to their children. Many of whom end up homeless despite being minors. Ngos such as L’Effet Morpho help children in such helpless situations.

The nuns:

The nuns that were the direct perpetrators of these atrocities — that are still alive and still in charge of the last active residential school — confessed to their wrongdoings but added that it was necessary to correct the children and give them a bright future. “These children are not civilized, we are trying to help and give them the tools to enter society. We want to give them what was given to us, a french education" says one of them. She then blamed indigenous families for giving a faulty education to children and not preparing them for the real world.

Sister M herself, who’s been operating in the first residential school in the territory more than 30 years ago says that it’s all very unfortunate and that no matter what may have happened it came from a place of honesty and a real desire to help.

Now due to the growing scrutiny they face regarding their actions, they feel trapped, and unable to interact with the children they’re supposed to take care of because they know that no matter what they do they will face severe backlash.

Recalling bittersweet memories of what has been lost:

A blue gown, white buttons facing upward, a blue belt; Removing each blade of grass, one by one, in the blistering sun — These are Kady’s earliest memories in the residential school of St-Laurent-Du-Maroni. Originally from the village of Awala-Yalimapo, along the Lawa river, and home to the Kali’na people, her family was coerced to give her away when she was 4. However, she doesn’t have any recollection of her life before she turned 8, saying the bulk of her early life resides in her sister’s memories of her constant cries.

“I don’t know what you did that day, but one time they punished you and had you remove each blade of grass from the garden under the sun; I told them it wasn’t fair and I would do it in your place but they refused.” her sister recalls.

“Even if there would be no grass in the garden we would have to do it, every time. Sometimes, we were forbidden to eat, or isolated from the others.” she adds.

Having only known the residential school system for her entire life at 15, at the time she couldn’t process the pain such a place created in her. It was only along the years, as the unconscious pain lingered in the back of her mind, that she started realizing the gravity of her past.

During the weekends she had permission to visit her parents, but as they had been forbidden to speak kali’na at the school, she progressively forgot her native tongue. She would never be able to communicate with her mother ever again. When visiting her parents who didn’t speak a word of French, she remembers to this day the pain of feeling like a stranger to them — being unable to tell them how she is, who she is, what her life is like, and vice versa — only being able to answer in yes and noes.

At the tender age of 12 her mother died while she was in the Home. She was unable to properly communicate nor grieve with her father until she was much older and able to reclaim her culture.

This is the intended consequence of the residential school system in French Guiana, meant to weaken the bond between the culture, the children, the families, until after the parents and grandparents, the aunts, the uncles have passed, the culture is lost and only remains the civilized indian.

In the photo, she’s wearing one of the traditional shawls proudly worn among the First Nations. During her time in the residential school, this sacred piece of cloth was taken from them and hid away, only taken out when presenting them to visiting officials from the mainland or special occasion* — displaying them like animals in a zoo.

Many cultural and sacred artefacts of their culture were erased from their lives, from the face paintings that adorned their skins, to the length of their hair, worn with pride and dignity.

Guillaume Kouyouri was taken to the residential school of Iracoubo when he was 6. Being a Kali’na Tīlewuyu from one of the 5 remaining families of his region, to him, these ‘Homes’ represented the natural continuity of what the system had become. “Wake up, pray, eat, do your chores, go to school, survive” he says, survival being the key word here. Days were monotonous in the pain and treatments he and other children of the Home would be. “When you’re not in your natural environment, you can’t learn anything, you can’t exist.” He adds, then adding that it was a disembodied experience because of how little his existence meant to the priests. “We were treated like less than nothing, to them we were worthless.”

His life began to change around 13, when he decided against the priests’ will, to force himself to learn his culture and reclaim it, practicing it with other indigenous teens in secret.

The reason why, unlike north america, indigenous communities of France were never able to gain cause, is because France is fundamentally unable to recognize their rights because it would go against their politics of only one french people, united and undivided.

This policy of unification at all cost is at the root of the impossibility to bring about any meaningful acknowledgement from the government, and with that reparations. That and it would be having to acknowledge the current atrocities happening in St-Georges-de-L’Oyapock to indigenous children of the Amazon.

Today, many indigenous individuals across all generations suffer from the legacy of this lingering system, trapped within a limbo of painful memories and the inability to move forward due to the lack of accountability. They lack a voice and a say regarding the affairs of their own people. It would be fair to say that unlike Canada and the US, agency is a right they’ve lost a long time ago and never got back. Even the rest of the population is unaware of all the atrocities.

Moreover, it isn’t just the residential school system and its legacy, but all the parallel institutions they must face, such as still having to live far from their parents for high school or university in host families that only sees them as sources of funds and glorified maids, or the lack of future prospects the youth faces when they decide to move back to their villages, leading to yearly waves of mass suicides due to the profound feeling of inadequacy, the constant shutting down and censoring of their plight from those with power, the lack of support and the willful denial of their very existence by the nation that once tried to destroy them. Generational trauma isn’t just something that was carried from the past, it is ever present, and with the challenges they face, self-reinforcing.

And the children are suffering and dying because of it, and no one will say anything because it is not overt — because of the false belief somebody else will take care of it, or talk about this story.

No matter who you ask within indigenous communities of French Guiana, there’s this, ongoing, sundering sense of dismay within their hearts, for all the lives that have been and will be lost.

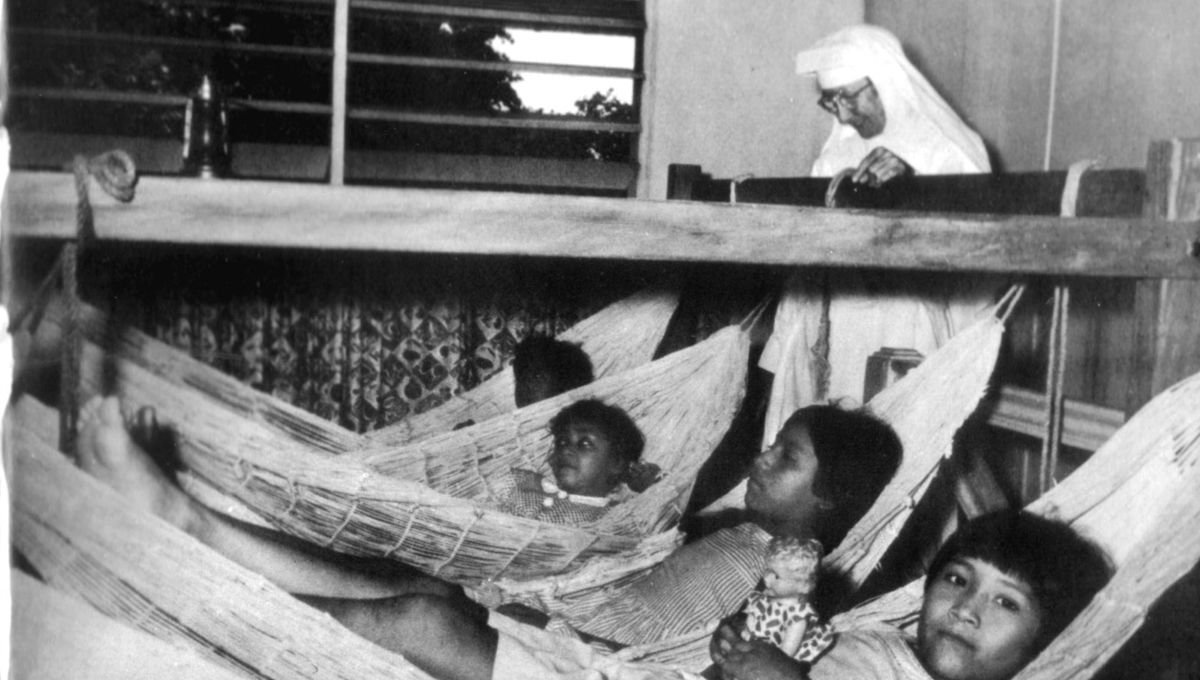

“I was never able to be with my mother the same way, she became a stranger and it broke me.” says Alexandre, 56 years old, crying as he tells the story of the hammock he’s clinging on, that his mom wove for him 50 years ago before he went away.

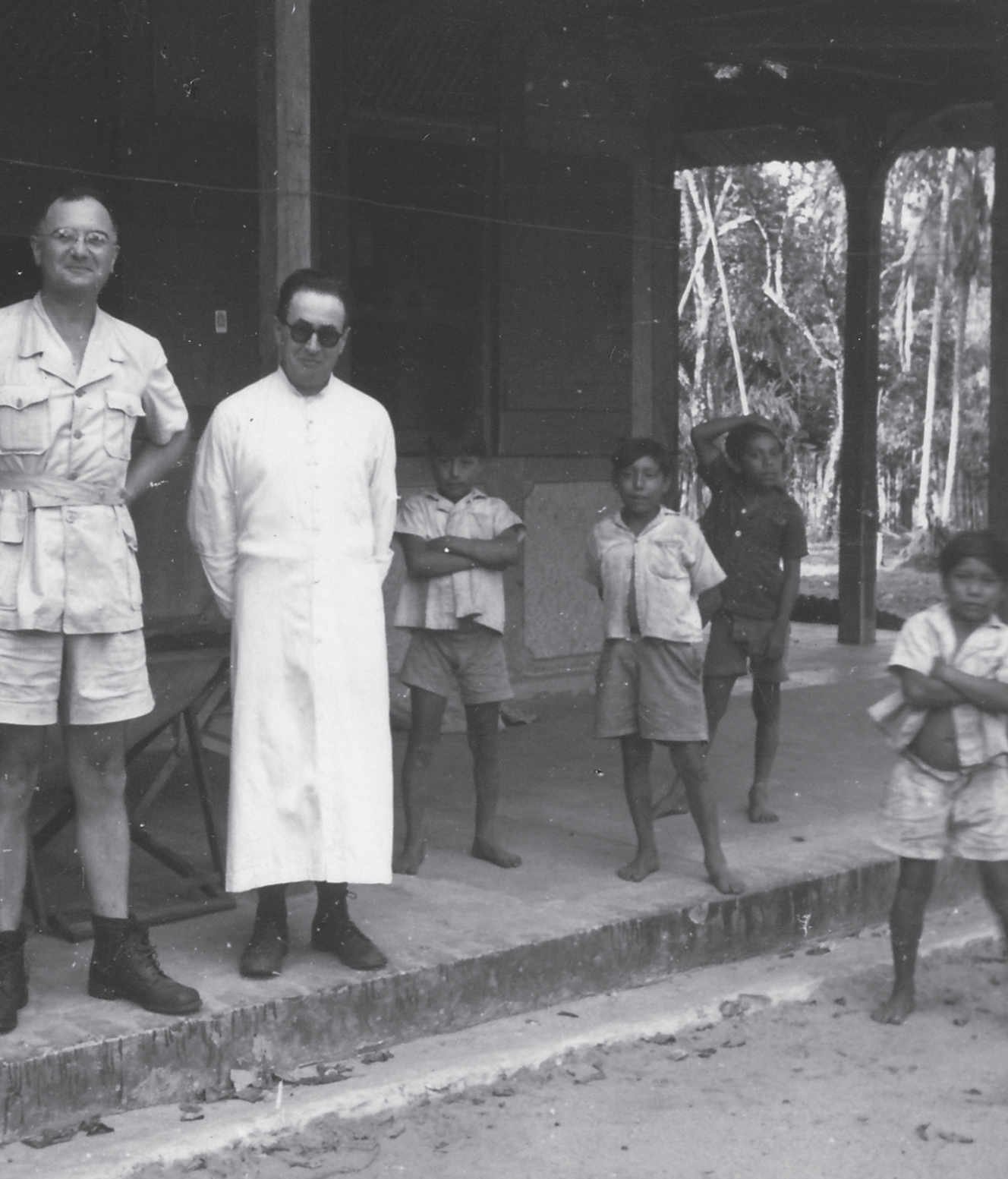

Three children walking inside the residential school.

Indigenous children of these ‘Homes’ are known for running away. Often in an attempt to go back to their families in vain.

I talked to a nun, sister Bénédicte, who was fairly transparent of the nuns’ treatment of indigenous children. Often justifying it with the need to discipline them, since they do not listen and do not know how to behave themselves in society. But now there’s so much scrutiny around these homes that the nuns have started to keep a low profile. They seem to be torn between the call to save the children and the reality that these children’s situation entails.

Establishments like these are at the forefront of the waves of mass suicides indigenous communities of the region have been facing for years, due to loss of their cultures and being displaced from their family to come back to the lack of any positive prospects for them.

Cristína. Member of the Kali’na people, her family fled French Guiana to escape from the atrocities of the residential school her mother and grand mother were parts of. She now lives in Oiapoque, a brazilian town across the French-Brazil border where she now enjoys a peaceful life.

Since former residents and their families have been coming forward just now, we’re starting to piece together the full extent of the damages Homes did throughout the years.

Before sunbreak, indigenous children from the village of Trois-Palétuviers preparing to go to school at 6am (45min boat ride to St-Georges). Some of these children used to eat for lunch in the residential school. Many of their elders and parents went to the residential school as well but as time went by less and less residents from the village needed to go.

Photo of sister M, who used to be part of the residential school system 30 years ago.

“It’s unfortunate they (indigenous communities) reacted this way, you spend your entire life caring for them and that’s what happens.”

Notes: nuns unable to accept the reality of their acts

They acted from a pov of love and care regardless of the reality of the culture but didn’t realize their acts were instrumental in creating a dead end society

Guillaume’s land.

*Theme of reparation and the land of indigenous communities and how it’s been stolen.

Photo of a school boat from the village of Trois-Palétuviers going to St-Georges to drop children of the village. While the residents of the residential school all come from Trois-Sauts, some of the residents of their village used to go to the residential school. The children/teens on board are familiar themselves as some of them used to eat there for lunch. There’s a clear divide between them and the children of the same age at the residential school since the nuns have forbade the children to interact with non residents outside of school hours.

Families of Trois-Saut during a brief stay in St-Georges.

Since the children of the residential school are from Trois-Saut, during back to school time, their families go through a 3 day long journey to St-Georges that can up to 2 thousands euros to drop their children who’ll stay there for the next few years. They gather in St-Georges in flocks for a brief time and then go back home on that same journey. All of the children going to the residential school won’t be able to talk to their parents for months due to the lack of reception/internet in Trois-Saut.

When children of either the residential school of St-Georges or the host families of the littoral are kicked out of their place of stay by either the nuns/priests or the families, parents have no way of knowing what happens to their children. Many of whom end up homeless despite being minors. Ngos such as L’Effet Morpho help children in such helpless situations.

Dylan (fake name), a 17yo from the wayapi people, he used to go to the Residential school of St-Georges until last year. He stayed 3 years. He suffered physical punishments and witnessed the same violent and humiliating treatment that occurred for decades on himself and on his friends and community.

Quotes (recording available):

“If we were between us we’d speak wayapi but if not we had to speak french (…) we’re told we have to speak french. (…) she’d tell us ‘speak french’.”

“One time we were praying and I laughed, she pulled my shirt and told me she’d rip my ear.”

When asked if he already received physical punishment he nodded yes. When asked how he felt when that would happen he said “I was angry, a lot of time I wanted to hit her back.”

“I’m not the only one (who would flee), several others would too.”

“Sometimes we had to steal food in the pantry because we were hungry.” (They would steal ingredients from it and give it to a janitor/surveillant to cook it for them secretly and give it to them the next day).

“Once, she (the sister) took a piece of bread from the trash and told him (a resident) to eat it.”

“The punishments we got were not being able to eat dinner, to clean, but if you’re punished it’s forever.”

“every morning we have to get up at 5am, pray and clean three times per day.”

I met him via the NGO L’Effet Morpho.

Traditional indigenous hammock. Made from a special cotton fiber. The creation of these hammocks is rare nowadays.

Alexis Tiouka, indigenous activist who went to the residential school of Mana at 6 years old.

Quotes:

“When we arrived, they would cut our hair. It was humiliating because our hair is our pride and they were aware of that.”

“The goal was to kill the indian and keep the man.”

(Will add his story here)

Seeds of roucou. Roucou is a cultural marker that is used as a red pigment by indigenous tribes of the Amazon. Indigenous children of the residential schools were forbidden to wear any.

Notes: The problem with French accountability and why everyone is so afraid to change anything and face the truth compared to Canada.

Big diff with Canada in how the higher ups tackle the question of indigenous communities.

Some gov head said there are no indigenous ppl in France.

Theme of national unity at all cost at the expense of others.

How it reinforces the problems of Homes and the plight of the first nations here.

Growth of him and his people stunted by post colonial legacy still going on today.

France diluted their influence and people.